Blog

Past, Present & Future Implications for Family Independence & Well-Being

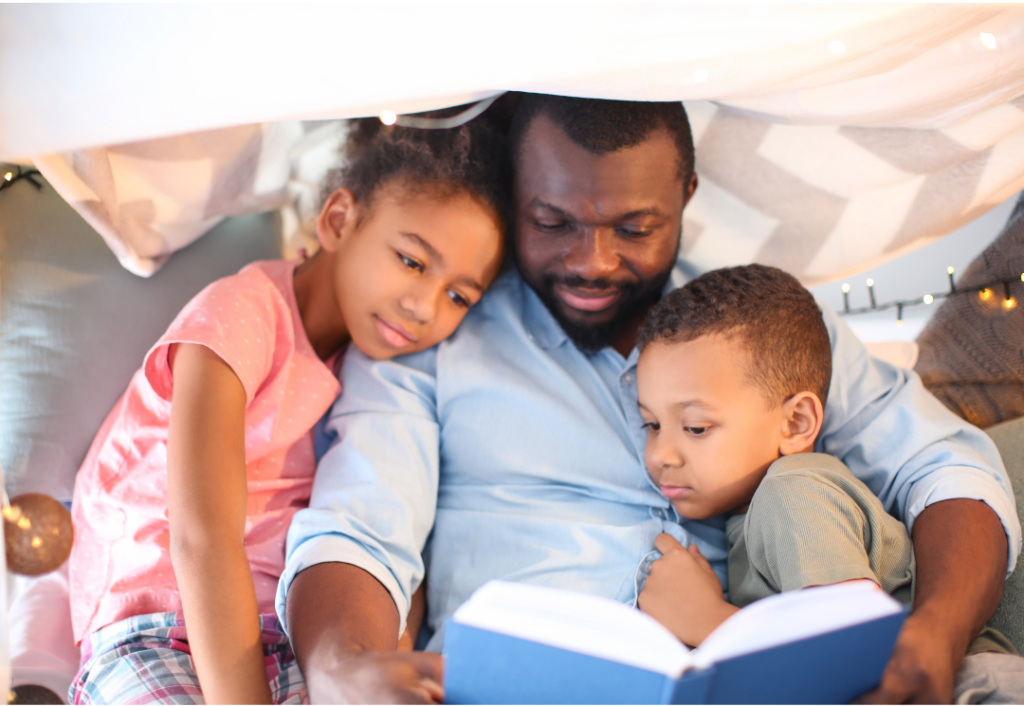

The rich, age-old practice of kinship care has not only acted as a means to maintaining generational connections to family and culture, but also proven to reduce trauma and result in better outcomes for children and youth needing out-of-home care. Yet, child welfare has only recently begun widely recognizing and valuing it as a formal, essential practice and option for families.

As we understand the critical need for kinship prioritization within child welfare, the onus has fallen on industry thought leaders and kinship advocates to address with policymakers the positive impacts of kinship care on the overall well-being of children and families.

In celebration and recognition of the strides kinship care has made over the last few decades—with the understanding that there is still much to be done—ASCI spoke with its founder, president and CEO Dr. Sharon McDaniel and Dr. Joseph Crumbley, kinship care expert, trainer, therapist and consultant, to highlight what has changed, the work we still need to do, and what they hope to see in the future of kinship care.

Dr. Sharon McDaniel

Dr. Joseph Crumbley

History and Implications of Past Kinship Care Policy

With their combined decades of service, education and dedication to kinship care, both Dr. McDaniel and Dr. Crumbley have witnessed the evolution of kinship care within policy and its perception within child welfare, as well as believe in the power and resilience of families to influence policy change.

“When I think about beginning in kinship care, I think back to family preservation,” Dr. Crumbley begins. “I’m thinking back to ASFA—the Adoptions and Safe Families Act. Those are my beginning years when those policies were being developed and affecting kinship care. And, what resonated for me back then was the idea that when children aren’t able to return to birth parents, then the preferable option and alternative should be family. That’s always been a guiding principle for me. That directed my work, and it was that belief that if not parents, then family [should care for the children]. The importance of family resonated with me.”

He continues, “I think kinship care should no longer be looked at as an alternative family. But really, it needs to be looked at as a mainstream family, just as the nuclear families—two-parent families and single-parent-headed households. [Kinship] no longer should be viewed as alternative or temporary, but as traditional mainstream families that need to be supported as a mainstream family. Because they’re not going away. Kinship families are not going away. It’s cross-cultural, it’s cross-racial, it’s international. So, I think we need to support kinship families as we would any traditional mainstream family. I think that’s the lesson that we’re starting to realize now and what we need to learn. And the legislation needs to support kinship families as traditional families, as well.”

[Kinship] no longer should be viewed as alternative or temporary, but as traditional mainstream families that need to be supported as a mainstream family. Because they’re not going away. Kinship families are not going away. It’s cross-cultural, it’s cross-racial, it’s international.

Dr. Joseph Crumbley

Echoing this, Dr. McDaniel highlights the critical need to center the resilience and strengths of kinship families in the work in order to provide them intentional supports, a lesson she learned early in her career. “Families matter,” she begins.

“Protecting and uplifting kinship families is critical, as they have been the safety net for many communities. And as [Dr. Crumbley] said, it’s international. It’s not restricted by boundaries or geographic regions. Young people come from families. And so, one of the things that I learned early on in child welfare is that you must be intentional with ensuring that families are present. Families are centered on what you do in child welfare. And unfortunately, I still think there’s that struggle because [people] still think about, ‘the apple not falling too far away from the tree.’ I think that that ad remains. In particular, some regions around the nation try to get you to prove something’s wrong, or that these families have to be fixed. So, this notion of having to ‘fix’ a family and looking at them through that pathological lens versus a resiliency lens is still present. You must value family. You must see that they are resilient, that they are supportive.”

“Families matter…protecting and uplifting kinship families is critical, as they have been the safety net for many communities.”

DR. SHARON MCDANIEL

Dr. McDaniel alludes to Dr. Robert Hill’s books, The Strengths of Black Families and The Strengths of African-American Families: Twenty-Five Years Later, to emphasize the need to remain dedicated to policy changes that support families through a strengths-based approach as opposed to the historically race-biased, deficit-based approach that has worked to punish families instead of support them.

“[These books] really helped to center the importance of family and the work that I do today,” Dr. McDaniel offers. “I think systems still need to do an examination, a self-examination of whether or not they have centered their policies and practices in the institution of the family. I think the federal government has done a remarkable job at looking at federal policies that support kin. Nonetheless, it still comes to a state’s decision and a jurisdiction’s decision whether or not they are going to embrace those federal policies. And I would offer that, unfortunately, we’re still having this debate about, ‘is kinship good?’”

Kinship Care Today: Dismantling the System

The more recent push to dismantle the child welfare system as it has been historically understood stems from its leaders’ intentional efforts to address the system’s racist structure, which has intentionally kept Black, Indigenous and Latinx children and families apart. In order to address the work that still needs to be accomplished with kinship care and child welfare in general, Dr. Crumbley explains that we must first focus on the institutional racism embedded in all American systems.

Federal policy would implement legislation conducive to kinship, but then the pendulum swung back when we didn’t see implementation of the policy on the state and county level…And that’s where we see prejudice and bias getting in the way of implementation.

DR. JOSEPH CRUMBLEY

“I think especially within the last year or two, issues of bias within the criminal justice system, issues of equity [and] the death of George Floyd have made us begin to look at institutional issues,” Dr. Crumbley explains. “For me, in child welfare, I think it’s important that we take it upon ourselves to look at institutional bias and inequities in our systems. Again, I think it goes right back to the biases and the inequities that we within the system have to challenge ourselves. When I think about what has occurred, consequently we’ve seen the pendulum swing in kinship care over the years—[the system] was supportive of kinship, and then for a while, it was ‘anti-kinship.’ And I think it’s because of that bias that exists. Occasionally, the pendulum begins to swing backward. Federal policy would implement legislation conducive to kinship, but then the pendulum swung back when we didn’t see implementation of the policy on the state and county level. We saw a federal policy, but then we saw a swing backward when it came down to financing and implementing the policy. And that’s where we see prejudice and bias getting in the way of implementation.”

Understanding the role that racism and bias has played in marginalizing BIPOC (i.e., Black, Indigenous and Other People of Color) kinship families and communities, both Dr. Crumbley and Dr. McDaniel expound upon the COVID-19 pandemic’s implications that further revealed these disparities and made the need for policy change more urgent than ever.

“We saw the response with COVID-19 and what is possible from the macro, federal level to the states and local jurisdictions,” Dr. McDaniel says. “Look at where the barriers are. Who are the gatekeepers who fail to ensure that the funding is taken down to the community level? And it’s all the biases that Dr. Crumbley discussed, from the macro to the micro. How do we disrupt and dismantle some of those gatekeepers who, for one, perhaps don’t believe in kinship care and have all those attitudes and behaviors that say, ‘No kinship care. No, not here,’ but yet disrupt the flow [of funds] to families?”

“We already had a study back in 1993 that helps us understand who the kinship caregivers are,” Dr. McDaniel continues. “They’re already marginalized. When you place a child without support, they’re further marginalized and we’re creating the next generation of the poor. So, we think about the caregiver who may have retired using their retirement to take care of their grandchild because there’s a bias in the system that says, ‘You do this because that’s your grandchild.’ But meanwhile, they’re on a limited income. We see that every day. We see the story of Ma’Khia Bryant. She was taken away from her grandmother because her grandmother didn’t have the resources, because the Ohio child welfare system did not give her the resources. She went to a foster home, got into an altercation and now she’s dead. We must look at the implications when we fail to see the broader picture.”

Dr. McDaniel further explains critical policy recommendations that would ensure new policies are culturally sensitive to BIPOC families and no longer intentionally separate them.

“The other thing I would offer is that we look to change MEPA/IEPA,” she says. “It was one of those policies that totally dismantled families of color. They didn’t care about young people maintaining their self-identity because they didn’t care where these young people were going. So, that’s a policy that I would offer at the federal level [to be changed], and then its interpretation across the state and jurisdictional level needs to be challenged. This policy is actually the antithesis of what kinship is really about, and this policy is dismantling and disrupting families of color at will.”

Reimagining Kinship for the Future: Creating Supportive Child Well-Being Systems

Both Dr. Crumbley and Dr. McDaniel posit that the historical construct of child welfare must be radically dismantled in order to place the needs of families first and reimagine kinship for the future.

“My whole idea is that child welfare would not be necessary,” Dr. McDaniel explains. “If we’re shifting to a well-being system, we’re looking at prevention, we’re looking at early intervention, we’re looking at ways in which the community can come back to the forefront and be participatory for the well-being of the family, the community. Think about Black Wall Street. Black Wall Street fought to take care of themselves. How do we get back there? That really is that radical movement that I’m referencing so that child welfare in its current construct will no longer be. Instead, we’ll have community welfare [led] by the community. We’ll have community support by the community. In 10 to 15 years, my hope is to abolish what is currently existing and go back to the notion of Black Wall Street and go back to the fact that communities, with the right support and understanding of who they are, can take care of their own and we no longer need to be surveilled.”

Dr. Crumbley shares that by empowering communities and creating equitable opportunities for them to support themselves, families can thrive independent of a child welfare system.

“To me, thinking about it at a macro federal level, we need to make it where families don’t need the child welfare system” Dr. Crumbley states. “Families should be able to support themselves economically. So, it’s [about] helping families upfront so they maintain their independence and are able to function independently. That means giving people livable wages. That means maintaining certain levels of housing. That means social guarantees: minimizing that property gap, that educational gap, that wealth gap. It means families having their own, and owning their own and being educated to be independent.”

Reflecting upon the successes of kinship care over the years, Dr. McDaniel explains the power that kinship has had in influencing necessary policy changes that are essentially working to support families’ overall well-being.

“I think the biggest milestone [in kinship care] is that we’re still here. We’re still having a conversation.”

Dr. Sharon McDaniel

“I think the biggest milestone [in kinship care] is that we’re still here. We’re still having a conversation, right?” Dr. McDaniel says. “As Dr. Crumbley explained, the pendulum swings and shifts. But what has been interesting and particularly, when we think about the Family First legislation, Family is always first and should have always been first. So, we’re seeing the power of kinship care. We’re seeing through data the fact that young people, whether they’re adopted at 1 year old, they’re going to go and try to find their biological family because, at the end of the day, family matters, and DNA is stronger than any court order. Because child welfare has failed the larger community, child welfare has failed young people, we’re shifting to well-being. But what does that really mean? It must be defined by the constituents of the service. Now you’re seeing lived experience, lived expertise, being centered in policy formation and in these conversations. Now, you have this shift of power.”

While there is still much work to be done, the resilience of kinship families remains. By shifting power back to the family, kinship care will lead the way by demonstrating how we must break down systemic barriers for families to truly live and thrive independently.